“At their worst, superhero stories are just dopey male power fantasies, but at their best (see: Watchmen, Daredevil: Born Again, etc.) these myths don’t just entertain, they work as powerful allegories that help us understand who we are.”

– Brian K. Vaughan, March 2005

|

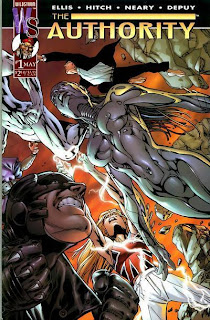

| The comic that helped define the 2000's |

In a way, The Authority has come to define this era of superhero comics, much as how, in past decades, other comics have defined their own eras. Just off the top of my head, we’ve got Fantastic Four #1 in the ‘60s defining the Silver Age of comics; perhaps “The Death of Gwen Stacy” story in Amazing Spider-Man that sort of marked the end of the Silver Age; the Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams Green Lantern/Green Arrow “Hard-Traveling Heroes” run that remains the iconic watermark of the socially-conscious comics of the ‘70s; Uncanny X-Men and The New Teen Titans, both of them prime examples of soap operatic serials filled with long-gestating subplots and melodramatic arcs, punctuated by watershed moments of overwrought characterization, came to heavily influence the superhero comics of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s; Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, both of which are two of the most deservedly seminal comics not only of the superhero genre, but of the medium itself (both were partly responsible for opening the floodgates of so-called grim and gritty superhero comics); the early ‘90s Image comics, which practically led to an entire generation weaned on style over substance; and, as the mentioned in the premise of this post, The Authority.

Whew! That’s quite a list. (I make no claims on being definitive. I simply wished to point out that there are certain comics that could be looked at as embodying the zeitgeist, if not kickstarting it altogether.)

And you know what Uncle Ben always liked to say… “With great power there must also come—great responsibility!” (Also, it’s one of the most slightly-misquoted phrases of all time. How many times have people quoted it as, “With great power comes great responsibility”?) While it probably isn’t right to hold The Authority responsible for the comics of the past decade, its influence is widespread.

|

| See? Read the last panel! |

In this post, I want to discuss some of the best post-Authority superhero comics thus far; superhero comics that are, for the most part, not based on any previously existing characters or titles. As a big reader and fan of the superhero genre, I have a lot of love for any top quality work, whether it’s done on a preexisting corporate-owned character or an entirely new creation. For the purposes of this post, however, I want to narrow my focus down to comics that are primarily new creations.

And this is not to say that all or any of these comics are directly influenced by The Authority at all. They just happened to be published after The Authority made its mark. Think of The Authority as the line of demarcation that begins this generation’s crop of superhero comics. So, as the decade draws to a close, I’d like to take some time out to look back on some of what I think are the best original superhero comics of the millennium, of the post-Authority era as I see it.

[A couple further caveats: I’m listing these in alphabetical order, not ranking them. Second, like any decent list, my list is meant to spark rational discourse. If there’s a series you think is worthy that I didn’t mention, that probably means I didn’t get a chance to read enough of it. (Or I have read it and just don’t think it’s any good.) Planetary, which is one of the most famous Ellis comics, isn’t on my list, not because it isn’t worthy, but only because it came out about the same time as The Authority, give or take a month if memory serves. I hate to be so anal about things, but I’ve got to draw a line somewhere. I’ll say right off the bat that there are some other Ellis comics that I haven’t read in their entirety that could very well be among some of the best superhero comics of the past several years, such as Black Summer, No Hero, and Supergod. The same goes with The Boys by Garth Ennis—what I have read of it, I really like, but I don’t feel like I’ve read enough of it to make any worthwhile comments. I haven’t read any of Mark Waid’s Irredeemable, either, just so you know.]

Enjoy the list, and click on any image to enlarge.

Enjoy the list, and click on any image to enlarge.

__________________________________________________________

1. Automatic Kafka (2002) by Joe Casey and Ashley Wood – What a shame this series has never been collected. It’s only nine issues long so it would fit in one nice volume. Wood’s avant-garde artwork remains unconventional for a superhero series, even one with a fairly complex style of writing. Automatic Kafka is probably Joe Casey at his purest and most unrestrained.

Ostensibly a story about a retired superhero from the ‘80s trying to move on with life, Automatic Kafka becomes some sort of metafictional statement from the creators about the state of the comics industry and the role of the superhero genre. I think the series “took place” within the WildStorm universe, as I remember the National Park Service was mentioned (including an agent seen in some of Casey’s Wildcats issues), but it felt divorced from any sort of awkward continuity, standing boldly on its own. Automatic Kafka is complicated and challenging to read, but also very rewarding. And the last issue is one of the most touching, elegiac send-offs for a fictional character you’re apt to find in any medium.

Automatic Kafka was published under WildStorm’s short-lived “Eye of the Storm” imprint. Surely that imprint wouldn’t have existed if The Authority had not pointed the way for more “mature” superhero works. While a number of mature readers superhero comics that came out in the wake of The Authority were ultimately hollow affairs, serving as showcases for unrestrained gore, violence, nudity, and sex, Automatic Kafka respected its readers’ intelligence. Casey and Wood certainly crafted an unusual and experimental superhero comic, and while it did have its share of violence and sex, it all served a point in the story.

|

| The cover to The Atomics trade paperback |

2. The Atomics (2000) by Mike Allred – The inclusion of The Atomics may be a bit of a cheat, as this fifteen-issue series (also available in one handy trade paperback under the title “Madman and the Atomics”) is a really spinoff of Allred’s superb Madman series. Keeping in tone with the relative lightness of Madman (who also appears generously throughout), The Atomics are a group of mutant street beatniks who decide to use their powers for good. Yup. Mutant street beatniks. You gotta love Allred’s boundless imagination.

He also does some excellent work in this series paying homage to classic superhero comics, such as with his Plastic Man pastiche, Mr. Gum, and with the general tone of the characters’ adventures (lighthearted and filled with humor, almost naively a throwback to the Golden/Silver Ages, but earnest and with sincere emotion).

You could almost say that The Atomics is the anti-Authority, in that it exhibits none of the style and none of the content inherent in The Authority. Even Allred’s stylish pop art looks like it’s from a different time period from Hitch’s superheroic realism. And while Allred opens up his art often, varying his grids and panel layouts, and allows his pictures to tell the story without any text, it’d be tough to consider The Atomics to be in any way decompressed.

3. Codeflesh (2001) by Joe Casey and Charlie Adlard – Codeflesh is a fairly obscure series that was published in an Image anthology in the early 2000s. It’s about a guy named Cameron, a bail bondsman in Los Angeles, whose specialty is superhuman criminals. The catch is that Cameron doesn’t hire a bounty hunter when his superhuman criminals try to skip out—he’s his own bounty hunter and he wears a pretty badass mask with a barcode for a face.

This sounds like a simple enough premise, and it’s one Casey would later revisit in 2008’s Nixon’s Pals. The stories are executed well, as the level of craft is top notch. Adlard’s artwork is particularly strong. He draws visceral scenes of violence, and he captures the grittiness of the settings. While the violence is hard-hitting, it’s more street level. Adlard also does a fantastic job drawing people, and their body language and facial expressions feel intuitive. His storytelling skills are commendable, as any reader of The Walking Dead can attest.

|

| Adlard's art perfectly captures the grittiness and tenderness |

While Codeflesh and The Authority both contain some pretty intense scenes of violence and have a certain brand of swagger, the scale of the stories is pretty different and I don’t really see much that they share in common beyond those superficialities. Nonetheless, Codeflesh serves a worthwhile counterpoint to the large scale theatrics of The Authority.

Image recently reprinted Codeflesh in a brand new definitive hardcover edition, complete with a new short story.

4. The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist (2004) by Various Writers and Artists – Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, is the inspiration behind this Dark Horse Comics anthology. The novel itself was a great American epic, and also a love letter to the comics medium. The main characters of the novel created a comic book superhero, the Escapist, and that’s what this anthology was all about.

|

| The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel |

The problem with most anthologies is consistency. The art of the short story seems to be a difficult one for many creators to perfect, and while this anthology wasn’t always perfect, it maintained an insanely high level of quality throughout.

Also of note is The Escapists, by Brian K. Vaughan, whose first chapter was published in the final issue of the anthology before it was canceled. (The Escapists was later published as its own miniseries before getting an attractive hardcover treatment.)

As a non-Marvel/DC superhero comic of the Post-Authority Era, The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist doesn’t try in the least to imitate current trends. It almost feels like a throwback, with many stories feeling like retro stories done with modern sensibilities. Regardless of how out of place it might appear on the surface, these are some mighty fine comics.

5. Ex Machina (2004) by Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris – This exquisite creator-owned series recently ran to its conclusion earlier this year. Not “merely” a superhero comic, this is a science fiction story about municipal politics in a post-9/11 world.

I don’t know if The Authority exerted any sort of overt influence into the shaping of Ex Machina, but I find it very interesting that the latter series is so distinctly post-9/11. That’s a stark contrast to the original Ellis/Hitch run on The Authority, which (in retrospect) sort of treats terrorism in general as a supervillain to be punched fearlessly in the face. That first issue of Ex Machina will always stand out to me as one of the most powerful, unexpected, and ballsiest things I’ve ever read. The whole notion of a superhero using any means necessary to improve the world is distinctly Authority-ish (Authoritarian?) and certainly by the end of Ex Machina we can see some character traits that call to mind The Authority.

6. Gødland (2005) by Joe Casey and Tom Scioli – Yet another Joe Casey comic. (He’ll show up at least one more time in this article.) Casey has lots of great ideas and his execution, more often than not, is energetic and impassioned. I feel that very few creators can match him in creativity and energy level. Gødland, an obviously Kirby-influenced cosmic superhero series (possibly also influenced to some degree by Jim Starlin), is genuinely exciting.

Scioli’s impression of Jack Kirby is impressive and a visually pleasing style. His artwork gives off that retro Silver Age vibe, where ideas are massive, imagination is boundless, energy cackles wildly, characters are all heart, and action howls off the page. The story feels like a mash-up of Fantastic Four and the Fourth World. And while the story and artwork are rooted in Kirby (Casey and Scioli even work old-school "Marvel style" where Casey writes a general page outline, Scioli interprets it on the artboard, and Casey goes back to it and inserts the words), there’s a modern sensibility that makes Gødland like no other series. You know how people often say that Grant Morrison can be absurdly insane in terms of generating ideas and concepts? People don’t give Casey enough credit. He’s like the American Morrison.

Thematically, Gødland is probably about change, and that’s something that was deeply integrated in The Authority’s DNA as well. Honestly, I can’t really think of any other ways to really compare Gødland to the Ellis/Hitch Authority. They are both such different books that I doubt Casey was directly influenced by The Authority. Unless he was influenced to create a comic that was almost the total opposite in terms of flavor and style, that is. The villains in Gødland are mean, and the action is bombastic, but I think the villains lack that depraved, mean edge that were critical to Kaizen Gamorra and Sliding Albion in The Authority’s first two stories.

Image Comics has the first issue up for free if you’re willing to have your imagination blown away:

http://www.imagecomics.com/iconline.php?title=godland_001&page=cover

http://www.imagecomics.com/iconline.php?title=godland_001&page=cover

7. Gotham Central (2003) by Ed Brubaker, Greg Rucka, Michael Lark, Stefano Gaudiano, Kano, et al. – All right, so Gotham Central may somewhat break my criteria for being a “new creation” but bear with me. Batman obviously played a role in this 40-issue series, but he was far from the focal point, and although some of the main characters were pre-established (such as Renee Montoya, Maggie Sawyer, and Crispus Allen—though he was created by Rucka a couple years prior), I’m giving Gotham Central some credit, partly for being such a unique superhero comic, partly for being such a great crime comic, but mostly because it’s great comics.

And that’s part of the thing with Gotham Central. I figure there are a couple ways to look at it. You can look at it as a crime comic or you can look at it as a superhero comic. I think the natural instinct is to look at it as a crime comic, or a police procedural. And that’s totally fine. I agree with that. But I also think it has some merit as a superhero comic. I think this is a fair assessment because it does have some interesting things to say about the superhero genre.

One of the things that springs to mind in discussing Gotham Central’s superheroic qualities is definitely its portrayal of Batman. I think he’s portrayed as a very Authority-like (Authoritarian? I’m think I’m just gonna start using that term!) figure. He isn’t a killer and he isn’t a metahuman person of mass destruction, but a number of the “normal” characters in the series, the detectives, view him as someone to fear. Batman is looked upon as someone who thinks he is above the laws and rules of society, someone who does whatever he wants, whenever he wants, however he wants. Even though he seeks to protect Gotham and its people, he’s still demonized for his actions by some of the characters.

There are moments in the series where the detectives are simply overmatched by the freaks of Gotham, and even though Batman swoops in and saves the day, it’s not like the detectives appreciate being shown up like that. The series’ opening two-parter, in which the police chase after Mr. Freeze after he has killed one of their own, particularly stands out as being a story that kind of shows the Authoritarian Batman. There’s also a later issue in which the police commissioner dismantles the Bat Signal out of disgust at how Batman operates. It all makes for fascinating drama.

I don’t know that this type of stuff is actually influenced by The Authority at all, but I think it’s one way of looking at the series as a whole in light of the era in which it was produced.

8. Hero Squared (2005) by Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, and Joe Abraham – Boom! Studios had a real gem with this superhero series about an alternate dimension superman from a decimated reality who gets trapped in a dimension in which his alternate self is just a regular unheroic schmoe. Hijinks ensue.

Truth be told, Hero Squared has more in common with Giffen and DeMatteis’ iconic Justice League (JLI/JLE) comics from the late eighties. (And briefly revisited in modern terms in the early 2000s with Formerly Known as the Justice League and I Can’t Believe It’s Not the Justice League.) Hero Squared feels more like a buddy/odd couple sitcom that happens to be steeped in the various tropes of the superhero genre. I don’t know if that was a natural reaction on the creators’ part intentionally to make a story that didn’t have the, shall we say, “meanness” and harder edge of The Authority. It very well could have been a simple desire to tell a story reminiscent of some of their previous work.

There’s also a lot of dialogue in this book. Much of it is funny. Much of it builds the characters and their relationships to each other, whereas The Authority often used a minimal amount of dialogue to convey that sort of information. (By the way, I’m not saying one style of storytelling, with more or less words, is more worthwhile than the other. These conventions are just different tools that creators can choose to use at their disposal.)

|

| An amusing sequence |

|

| Click to enlarge |

Compared to most other comics of the Post-Authority Era, Hero Squared is drenched in word balloons. I remember when Brian Michael Bendis was breaking into mainstream comics with his Marvel work, readers often criticized his stuff ‘cause he had a lot of “talking head” scenes. Hero Squared would give Bendis a run for his money. It’s funny because a lot older comics (like from the eighties or sixties) often had a lot of words, too. But it was like, when The Authority struck it big, people started to favor terser scripts. A lot of superhero comics from the past ten years or so are really fast reads as a result, and most of them don’t have the natural advantage of having a Bryan Hitch-caliber artist illustrating them.

I must also add that you definitely get your bang for the buck with Hero Squared because an issue will take more than 7 minutes to read and enjoy.

9. The Intimates (2005) by Joe Casey, Giuseppe Camuncoli, and some other artists – The Intimates, another WildStorm book, was a series that I think we can safely say was affected by The Authority to some degree. I remember reading some interviews with Casey around the launch of this book where he mentioned how he was trying to think of the antithesis of The Ultimates by Marvel (which is quite possibly the embodiment of the post-Authority superhero comic in the sense that it took most of the conventions of the first series and applied them as hard as it could). So The Intimates is Casey’s direct response to that. Essentially, it’s a teen superhero team book where the point is that nothing important is meant to happen.

True, it takes place in the WildStorm Universe, and latter issues even featured appearances from other characters Casey had written, such as Jack Marlowe (Spartan) from Wildcats/Wildcats Version 3.0 and Desmond (from Mr. Majestic). Regardless, the established universe backdrop is such a small portion of the book that it’s barely worth mentioning.

Casey tried out some interesting storytelling techniques in this series. Most notably, the bottom of every page featured an “info scroll” filled with a bunch of text. Sometimes the information in the info scrolls would provide footnotes or related anecdotes to the main action. Sometimes they would provide random trivia or other unexpected bits of wisdom. In the final issue, Casey breaks the fourth wall and addresses some of the issues surrounding the cancellation of the series. At the time, it was enough to make me wonder if the editors actually read his info scroll text. I believe The Intimates was the last book Casey ever wrote for WildStorm, and until recently (Final Crisis Aftermath: Dance and an editorially-screwed up arc on Superman/Batman) the last thing he did for DC.

I also remember the sixth issue of this series being particularly outstanding, as Casey and Cammo told the origin story of one of the characters by literally diving into his head (which was encased in something called a “null field”). It was nonlinear storytelling without the info scrolls for the most part, and at the time I felt like it was extremely dense for a 22 page teen superhero team comic. As an exercise in craft, it’s very impressive, but that issue also had some heart to it, which is always appreciated.

In a way, I guess The Intimates takes The Authority’s convention of using minimal text to convey the most information to the reader and flips that around. So in The Intimates, the tendency is to get bombarded with text, but a lot of that text isn’t always necessary to the flow of the actual story. The Intimates also eschews the glorification of violence in favor of the characters sitting around and talking.

From my description, it sounds like The Intimates is kinda boring. While I will certainly concede it is an experiment disguised as a commercial series (Jim Lee even designed many, if not all, of the characters and he drew the covers and a comic-within-the-comic), it remains steeped well enough in the world of superhero comics that makes it worthwhile reading for anyone who cares to have to think about the things they read, even superhero comics. Unfortunately, it was never collected in any trade paperbacks, but the issues shouldn’t be too difficult to find.

10. Invincible (2003) by Robert Kirkman, Cory Walker, and Ryan Ottley – I was looking over my list of favorite post-Authority comics and one of the things I’ve noticed is that most of them don’t actually seem to have been influenced very much by the Authority, at least not in overt, obvious ways. Perhaps at first glance, Invincible, which is essentially a teen superhero (and coming-of-age) story in a sort of 2000’s Spider-Man mold, doesn’t really seem to have that much in common with The Authority.

In some ways, however, Invincible is a series that takes some of the most superficial aspects of The Authority and replicates them on its own terms. For example, the somewhat shocking level of violence exhibited at times in the pages of Invincible is something that hearkens back to The Authority. (In fact, despite Ottley’s cartoony style, there are some images of mayhem and destruction and pulverization that are more graphic than Hitch’s superheroic realism.) The fact that the brutality in Invincible is often treated so casually within the narrative tone of the story also reminds me of how The Authority treated violence.

Another reminder of The Authority is the character Omni-Man, Invincible’s father and an obvious analogue to Superman, just as Apollo of the Authority is a Superman-type character. Both Apollo and Omni-Man take the idea of a no-holds-barred Superman to the next extreme. They use their Superman-level powers in ways that you might actually expect such a powerful being to act without restraints. With a combination of invulnerability, superstrength, and superspeed, they can literally become speeding bullets and the results of that type of assault is quite devastating, as one can imagine. Certainly, Apollo and Omni-Man aren’t the only Superman analogues around, nor are they the only violent ones; but I do feel that after Ellis began treating Apollo as a weapon of mass destruction, or practically a world power unto himself, this sort of portrayal of the Superman-archetype has become more prolific in superhero comics of this past decade.

In terms of storytelling conventions, I feel that Invincible has less in common with the type of style that The Authority brought on. Invincible is more reminiscent of ‘80s and ‘90s superhero serials, with soap opera-type plotting (with a series of cliffhanger after cliffhanger, numerous subplots simmering in the background at any one time, and a plethora of characters inhabiting the world, each one ripe for another potential story). Like I glossed over earlier, Invincible sort of feels like a new school Spider-Man for this generation, a teen superhero who deals with being part of that superpowered world while juggling that with growing up.

11. The Moth (2004) by Steve Rude and Gary Martin – Let’s get this out of the way: Steve Rude is one of the greatest comic book artists who ever lived. He’s got a unique, beautiful style that, for some reason beyond my ken, isn’t as fashionable as it used to be. Nexus, the work he is best known for, is one of the best series of all time. So why doesn’t The Dude get enough respect? I have no idea. The comics market is just not fair.

The Moth is Jack Mahoney, a circus acrobat by day and costumed vigilante by night. His foes include (I’ll copy this straight off the back cover of the trade) “a savage lionman, a bounty-hunting thug, blood-thirsty mob hit men, and a trio of mischievous cat burglars! Toss in celebrity heroine American Liberty, an outlaw biker gang, circus hijinks, African witch doctors, and a bearded lady…” Come on, that sounds like fun! And I’ve gotta say, this comic has the most attractive bearded lady I’ve ever seen.

I remember reading some comments from The Dude (perhaps it was in a Nexus editorial) about how he was not too enamored by much of the current superhero comics on the rack today. It sounded as though he was remarking specifically about comics such as The Authority and The Ultimates. The Moth is a direct reaction to that type of storytelling and to that type of gritty, cynical, violent superhero.

It’s everything The Authority is not. Rather, The Moth hearkens back to the days of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, only these issues are done with a modern flair. Certainly, it’s nice to have options when it comes to superhero stories, and I wouldn’t want everything to be a pale imitation of one thing. Fortunately, The Moth delivers the thrills that many comics of the decade were too proud to offer.

12. Powers (2000) by Brian Michael Bendis and Michael Avon Oeming – (You gotta love those guys who go by three names, just like every famous killer in history.) Powers, like Gotham Central, is another one of those comics that straddles the genre line between crime and superheroes. Bendis and Oeming have used Powers, which mostly follows two detectives as they investigate superhuman crimes in an R-rated world populated with numerous superheroes, as a means of telling various types of stories about crime and about superheroes, and other stuff as well. (During a story that was practically about the history of the Powers world, they also created one of the most bizarre and controversial single issues of that year, the infamous “monkey sex” issue. It has to be read to be believed. But that’s practically a whole ‘nother topic!)

It feels wrong, somehow, to imply that Powers has been directly influenced by The Authority. So I will again reiterate that I’m not necessarily trying to compare every series on this list to The Authority, especially when Powers, in its own way, is perhaps just as influential on superhero comics of the past decade. But I’m simply using The Authority as a line of demarcation, and Powers was released slightly after The Authority (although I have no doubt it was gestating for quite some time in Bendis’ and Oeming’s minds).

If anything, Powers is rather appreciative of The Authority. An early issue even features Warren Ellis himself as a guest star, riding with the main character during a patrol.

That said, Powers and The Authority do share some things in common. One of the most obvious is the level of violence depicted (along with the profanities and vulgar language), although Powers is definitely more graphic, being a creator-owned indie series with no content restrictions while the original run of The Authority wasn’t allowed to completely cut loose. (It tended to imply things rather than outright show.)

|

| You must read to find out |

Both series, I feel, present a world that is harsh, depraved, cynical. Yet behind all of that superficial negativity, the creators seem to propagate a sense of optimism that underlies the surface thematically. It may not always come through cleanly but it’s there, it’s lurking, and it’s a big part of what makes it a pleasure to read stories that sometimes feature a whole bunch of horrible people doing horrible things to each other.

13. Runaways (2003) by Brian K. Vaughan, Adrian Alphona, et al. – BKV, probably more than any other Marvel writer, truly succeeded in creating a comic that was firmly set in the Marvel Universe but was also completely fresh and original. By subverting a classic theme of old-school superheroics (heroes fight for the memory of their parents, or because their parents tragically died), Vaughan flips the old paradigm with a simple but rebellious rock and roll aesthetic. The Runaways run because their parents are evil.

Vaughan’s Runaways stands out as one of the top Marvel series of the past decade. The book has a strong plot driving it and meaty characters who grow and change from their experiences. Some people think that Vaughan often tries too hard to throw in random, useless factoids into his writing just to show off how smart he is or something, but to me it simply feels like clever wit. There’s just an easy-going nature to his writing that makes his work a pleasure to read.

Where I think Runaways succeeds before many other superhero comics of the past few years is in its freshness. Although it feels familiar because it’s dressed in the tropes of the genre, its approach is offbeat enough that it also feels like something new. Certainly this is helped by the fact that the creators were firing on all cylinders as they produced this run of stories. This is definitely one thing that Runaways has in common with The Authority.

When The Authority came out, it wasn’t like it was something that completely rewrote the bible of superheroics. (In fact, we were somewhat prepared for it with the groundwork Ellis laid in StormWatch.) It was practically dressed like a normal superhero book, only Ellis and Hitch had caught lightning in a bottle and the work they did just felt fresh in context.

14. Sleeper (2003) by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips – (For completion’s sake, we can also toss in the prequel, Point Blank, by Brubaker and artist Colin Wilson, although that miniseries focused more on existing characters.) Sleeper, another WildStorm series, ran for two “seasons” of 12 issues each. I’m considering both seasons to be one series for the purpose of this article. Sleeper certainly has its roots in previously established characters. Two of the series’ main antagonists, John Lynch and Tao, are characters created early in WildStorm’s life cycle. Cole Cash, aka the Grifter, another major supporting character (and protagonist of Point Blank), was created in the very first WildStorm comic back in WildC.A.T.s #1. (Oh, nineties, with your ridiculous “hip” acronyms…)

Sleeper is known for being partly responsible for ushering the noir boom into comics today. It’s an amazingly fantastic comic and probably one of my all-time favorites, to be honest. Being set in a world of super-powered espionage, it’s also a superb spy comic and an excellent superhero comic. The superhero aspect feels a bit less important than the noir and the character study aspects of the story, but it can’t be ignored, either.

In a way, Sleeper presents the dark underbelly of the world that The Authority doesn’t have time to gloss over. The Authority was all about world-devastating threats: a terrorist nation with an army of supermen lashing out at the world; an invasion from the entire forces of a parallel Earth; and, essentially, Warren Ellis’ version of God. Sleeper tackles all the hidden stuff that the common man doesn’t even know exists, stuff like underground syndicates, covert ops, the secret monarchy of Earth, and so on.

Where The Authority really offers minimal development of its leads and focuses more on characterization through action, Sleeper takes the time to flesh out its characters, providing backstories and origins and plenty of development. A lot of the supervillains in Sleeper have that hard, mean edge that The Authority’s villains also share.

The series could be looked upon as a character study. Holden Carver, the protagonist, is a deep cover operative who has infiltrated a supervillain organization but his handler, John Lynch, the only person who knows he is a sleeper agent, is put into a coma. So nobody knows Holden is really a sleeper agent, and he’s forced to do terrible things to stay alive, things that erode his soul. At the very end of Season One, his handler awakens from the coma, and then Season Two is mostly about Holden trying his damndest not to be a pawn between the machinations of Lynch and Tao, who runs the criminal organization Lynch has been trying to destroy.

Brubaker and Phillips use this premise to explore what it means for a man to do these horrible things to stay alive, and how it changes him. It’s a character study of a good person who plays the role of a bad person, only he comes to depend on playing that role in order to preserve his own life, and eventually gets to the point where even he’s not sure if he’s really a bad person or if he’s still playing a role, or if it’s even worth trying to go back and try to become that good man again. Layered and complex, Sleeper is deeply compelling, with some tremendous artwork that adds even more texture to the storytelling.

(Brubaker and Phillips are currently working on a sort of counterpoint to Sleeper with their current series of miniseries, Incognito at Marvel’s Icon imprint. It’s well worth checking out.)

15. The Umbrella Academy (2007) by Gerard Way and Gabriel Bá – So far, this pair of six-issue miniseries (and a few short stories) has proven to be this generation’s Doom Patrol. The (Eisner Award-winning) Umbrella Academy is creatively quirky in a way that calls to mind Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol back in the late ‘80s and Arnold Drake’s Doom Patrol back in the ‘60s. The Umbrella Academy is the successor to those comics, and the landscape of superhero comics is all the greener for it.

Filled with eccentric heroes and villains, The Umbrella Academy revels in the spectacle of sheer wonder and temerity. I don’t think there’s anything quite like it today. It’s a comic that is clever and intelligent and full of pictures and ideas you have rarely seen before. Its tone varies from lighthearted and mirthful to dramatic and intense to tender and back again. Moving at a breakneck pace, it never loses its ability to thrill and move me.

Bá has been getting plenty of well-deserved accolades for his work, and it’s easy to see why he’s such a highly regarded talent when you look at any page of The Umbrella Academy. Also, Eisner Award-winning colorist Dave Stewart consistently injects everything with a whole lot of life and energy.

|

| Flashback: the young Umbrella Academy fights an animated Abe Lincoln monument (they fought the Eiffel Tower in volume one) |

|

| Read the comic to find out how they defeat this sinister threat |

If I had to make any sort of comparison to The Authority, I’d say the trait both books share in common is their audacity, their audacity to basically go back to the days when superheroes faced absurdly grand threats and laughed in the face of hopeless odds. The way the two comics go about in refracting these ideas is different, but not so dissimilar that you can’t like one without being able to appreciate the other, I think.

Gerard Way, who is also a rock star, has cited Morrison as a major influence, and you can trace the spiritual lineage through reading The Umbrella Academy. I must admit that after reading his comic, I gained a new respect for his music in the band My Chemical Romance. Way has mentioned that he has plans for eight or nine miniseries. I’m definitely looking forward to more.

16. Wanted (2003) by Mark Millar and J.G. Jones – There’s a lot that’s been said about Wanted. Much of it hinges on the last two pages of the story, which seems to offend many readers. I’ll get to that in a bit. (There was also a Hollywood version of this… only they took out the superheroes/supervillains and did some strange things with bullets, and I ended up not bothering to watch it.)

Wanted started off as a pitch for DC’s Secret Society of Supervillains. It ended up being a story full of obvious analogues for those DC supervillains and was published by Top Cow. (Perhaps Top Cow’s finest hour?) Millar is kind of a polarizing figure for a lot of fans (at least the outspoken ones who post on Internet messageboards), and I think that Wanted was the book that cemented that rep.

Wanted gets criticized all the time for being shallow and immature, full of sound and fury but signifying nothing. It’s also really, really dark and cynical in its worldview and it abounds in shocking violence, far more extreme on those terms than The Authority. I can easily understand why it wouldn’t be to everyone’s taste. For my money, though, it’s one of the most entertaining Post-Authority superhero comics around. (Steve Rude probably hates this if he’s ever laid eyes on it, though.)

So Wanted is a story about Wesley Gibson, a regular joe who is basically granted the ability and means to break all the rules of society when he gets inducted into a secret fraternity of supervillains. (They secretly run the world after brutally murdering all the superheroes years ago.) Wesley learns he can rob, murder, and rape anyone with carte blanche now that he’s part of this group. After a lifetime of being crapped on by the dreariness of ordinary living, he finds that his every fantasy can now be realized. It turns out that he’s a bastard who’s all too willing to live for himself.

This could all totally turn out to be a pointless comic, but it’s helped immensely by the talented J.G. Jones, who seemed to be able to really take his time on this. As a result, it looks really good. He does “widescreen action” as well as Bryan Hitch, and his character designs are memorable.

Like I said, I can understand that people might not enjoy Wanted because it does show a lot revelry in debauchery and depravity. It’s not very pretty, and the main characters are mostly all mean-spirited.

The thing I never understood, though, is when people take umbrage at the last two pages of the book. I’m guessing by this point in time you already know whether or not you enjoy Millar’s work in general. So I hope this isn’t too bad of a spoiler, but the last two pages were controversial. Wesley narrates a sequence of scenes, directly addressing the audience, detailing the pathetic existence of the humdrum of an ordinary life and boasting in his newfound glory. He goes so far as to proclaim that even the comic you are holding in your hands is simply an example of how hard he and his ilk are “working you.”

In the second-to-last panel of the comic, Wesley narrates, “You’re just going to close this book and buy something else to fill that big, empty void we’ve created in your life.”

The last page is a giant close-up of Wesley’s sneering, contorted face and shirtless torso with the text “This is my face while I’m fucking you in the ass.” And that’s it. The End. That’s how Wanted closes.

I think that a lot of people were upset by this because these last two pages, almost out of nowhere, seem to take the piss out of its core audience. Some readers probably even feel that Mark Millar himself was sticking them the middle finger with this scene, cruelly laughing at the people who buy his comics and support his work.

I’ve met Millar once, when he made an appearance at the Isotope, one of San Francisco’s best comic book shops. I had a chance to chat with him and I find it extremely hard to believe he is this cold-hearted jerk who disdains the very people who read his comics. He was nothing but amiable to me even though there was a throng of people around us. Throughout our conversation he displayed a warm sense of humor and a graciousness that I really doubt he faked.

Even if I weren’t testifying to Millar’s character, I honestly feel that those last two pages in Wanted aren’t a giant middle finger to the fans. First of all, I think it’s a knee-jerk reaction to assume that everything that comes out of a protagonist’s mouth is the writer speaking through his creation. Many times in fiction, that simply isn’t true. The character is not the creator.

Second, I feel that those last two pages are meant to embody what Wanted is all about. Thematically, the story is about how we, as people, want things we can’t or don’t have and want to do the things that we can’t do. Wesley is able to break free of his metaphorical chains and do the things he wants to do. That was what he wanted. The second-to-last page summarizes that and the final page seems to say that if we empathized with Wesley, we missed the point.

I mean, it’s natural to root for the protagonist, and Wesley wasn’t really too unlikeable in Wanted. But to empathize with him, to root for him, to want to emulate him the way we sometimes want to emulate our heroes, is just foolish. Not just foolish, but wrong. I get the sense that Millar is basically saying that it’s admirable to want a simple existence… because people who end up living for themselves turn out to be jerks like Wesley.

That’s what I make of the ending, anyway. I guess the easy counterpoint to my argument is to say that Millar didn’t do a very good job communicating all this in the text, or that he’s just a lazy/bad writer or whatever, but it was enough for me and that’s what I got out of it and that’s why I like Wanted.

17. X-Force and X-Statix (2001) by Peter Milligan and Mike Allred (with various other talented artists pitching in) – Eventually, at some point, I’d like to do a proper, more in-depth series of issue-by-issue commentary/reviews. I’ve made no secret of my love for Milligan’s work, and X-Statix (which began with X-Force #116) was absolute brilliance. (This includes the Marcos Martin-illustrated Doop short story in the semi-obscure My Mutant Heart one-shot as well as the X-Statix Presents: Dead Girl miniseries.)

Milligan’s writing in this series was deliciously unconventional, offering an outsider’s view of one of the most famous brands in all of superhero comics. Satirical, ironic, post-modern, full of wit and clever ideas, X-Statix is probably the closest thing to a Vertigo comic that Marvel has ever done, other than maybe Fantastic Four: Unstable Molecules by James Sturm and Guy Davis.

It’s a very subversive work because Allred’s art is so poppy, and it’s easy to assume the content of the stories would also be mainstream or retro. But Milligan takes convention and blasts it in the face. Their first issue of X-Force is so unlike just about any other superhero comic’s first issue. How refreshing it is in its willingness to not play to expectations. When Milligan and Allred took over the book, they pretty much threw out or ignored the previously established team and installed their own original quirky mutants as part of a new X-Force team. Then they brutally slaughtered almost everyone they painstakingly created before that first issue even ended, thus setting up the NEW new team! How absurd is that?

Throughout the course of the series, Milligan and Allred dealt with a variety of themes and topics. Probably one of the most central to the series was the theme of celebrity. While the X-Men are a group of mutants who are sworn to protect a world that hates and fears them, X-Force/X-Statix was a bunch of mutants who wanted to capitalize on their powers and become famous popstars. At the time, it was a fairly unusual take on superheroes, but logical if you think about it. This concept has become more commonplace over the past several years, but X-Statix had top tier execution.

Ellis and Hitch’s The Authority hinted at the idea that superheroes would be super famous the world over. Later creators, like Millar and Frank Quitely, who worked on the series after Ellis and Hitch left, would extend that idea further. In The Authority, the team is famous because they are super powerful and save the planet from unimaginable threats.

In X-Statix, the team is famous just for being the team… Sort of like how in the past decade, there’s been a bunch of people who are famous not because of anything significant they’ve accomplished, but just because. The proliferation of reality television and other inane forms of entertainment have resulted in a number of celebrities who seek attention and, for some reason or other, actually get it. A lot of the characters in X-Statix are just like that, and Milligan takes the piss out that notion constantly throughout the series. (Marvel’s excellent ten issue series from 2007, The Order by Matt Fraction and Barry Kitson, also dealt with the concept superhero celebrities, but usually with a more serious and traditional tone.)

This could all be very intellectual and detached but Milligan puts special effort into developing the characters and coming up with plots and storylines that drive and change them. It’s almost unfair when he kills off a major character near the end of X-Force, before the series was relaunched as X-Statix. That final X-Force storyline stands out as a powerful tale that moved me to tears.

|

| Mike Allred: one of my all-time top three Mormons ever (right up there with Orson Scott Card and Steve Young) |

Another funny thing is how a bunch of old X-Force fans were distraught at this new take on the team. Talk about totally missing the point. In the letters columns, people would write in complaining about the “weird stories” and “ugly art” and demand “their” X-Force back, complete with Cable, Shatterstar, Cannonball, Domino, and so on. It got to the point where I don’t think it’s unreasonable to suspect that Milligan himself wrote some of that hate mail as a parody of what people were probably feeling.

|

| Mr. Sensitive vs. Iron Man - Fight of the Century |

|

| Context: they're fighting on the grounds of a French religious extremist group who believe that God finds clothing offensive |

|

| There's more to it, and it's hilarious |

As the series progressed, I guess it became clear that sales were slipping and Milligan and Allred had to wrap things up, especially after word leaked out that they planned to feature a resurrected Princess Diana as a member of the team. Marvel backed down from that controversy and forced Milligan and Allred to change Princess Di to a fictional pop star, but I have a feeling that was the beginning of the end for the book. I mean, the stories were still just as good as before (the final arc was an epic and amusing battle between X-Statix and the Avengers), but once that happened it was like a blow to the company’s confidence in the title. And rather than allow the characters to languish, Milligan and Allred mercifully killed off the remaining cast in a memorable “downbeat but strangely moving” final issue.

They later revisited the team with the Dead Girl miniseries (ever notice how Dead Girl is sort of basically a female version of Allred’s Madman?). That miniseries parodied the idea of character deaths in superhero comics and did some pretty good stuff with Dr. Strange as well. Recently, Marvel released a teaser poster with an image of Doop (perhaps the iconic X-Statix character), hinting at plans for 2011. It’s something to look forward to in the next decade.

|

| All over the world |

Alan Moore’s ABC work was stupendous, too. Top 10, in particular, deserves its own entry as one of the finest superhero works of this era. I guess I didn’t include it because it came out very close to the time The Authority was launched back in 1999. Promethea, too, is worthy, although halfway through the series the superhero element gets pushed aside in favor of the metaphysical narrative. The ABC anthology Tomorrow Stories had some clever stuff, too, including some mind-expanding storytelling experiments in the Greyshirt feature. Of course, Tom Strong, a tribute to the pulp heroes of yesteryear, had some extraordinary stories over the course of its run, stories by Moore himself and some other writers. It’s all good, baby! Heck, I suppose you can even toss in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, if you want to imagine it as some sort of Victorian-era Justice League-type team.

|

| Them again, just because this is a cool picture |

No comments:

Post a Comment